by Franklin Burroughs

by Franklin Burroughs

Franklin Burroughs of Concord is an Adjunct Professor at John F. Kennedy University. At one time he lived in Iran for 15 years and served as the Executive director of U.S.-Iran Chamber of Commerce. He is also one of eleven local authors participating in the just-released anthology of short stories, “Insight, Hindsight, and Flights of Fancy ”.

Before the Islamic Revolution, Mohammed Reza Shah Pavli attempted to inform President Carter of his willingness to establish a constitutional monarchy. Soon after the Revolution, the Iranian military and Ayatollah Kazem Shariatmadari sought the assistance of the U.S. Government in initiating a coup against Khomeini and the Islamic Republic. In both instances, Burroughs served as the potential intermediary – an incredible diplomatic duty was placed upon his shoulders. He shared with Diablo Gazette his role between US and Iran, just weeks prior to the historic Islamic Revolution.

Concord Professor’s Historical Role – Rebuffed by Carter

Concord Professor’s Historical Role – Rebuffed by Carter

The opportunity to serve as a personal emissary between two heads of state briefly thrilled but later crushed me.

Jimmy Carter was elected president in 1976 and met with Mohammad Reza Pahlavi Twice in 1977. The first meeting took place in November of that year in Washington, D.C., the second in Tehran on New Year’s Eve 1978. During the November meeting, President Carter had declared Iran “an island of stability,” a declaration which indicated to the Shah that Mr. Carter viewed him as a significant ally.

Following the meeting in Tehran, however, the Shah became concerned about his relationship with Mr. Carter and fretted over the support he had thought he enjoyed from the United States. To the Shah, Mr. Carter had become less amicable and forthcoming between the Washington and Tehran meetings, and he couldn’t determine the reason for the change in attitude.

In March 1978, I interviewed the Shah concerning his views and thoughts on Iran-U.S. economic relations for publication in the local U.S. Chamber of Commerce Newsletter. Entering the office of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, I had no idea of what lay ahead. My sole purpose was to revel in the moment and realize a long-held desire to interview the reigning monarch of the kingdom that had intrigued me from childhood.

My intern, who that year was from Harvard University, accompanied me to the interview and took notes. As I posed my prepared questions, I sensed the Shah seemed bored and disengaged. He seemed interested in a topic or area other than what we were discussing. The Shah dismissed the intern but requested that I remain for a few minutes for a brief discussion.

“Would you be willing to represent him and his interests to President Jimmie Carter?” he asked me. This caught me completely off guard. Nervously, I asked what interests the Shah had in mind.

“I can’t seem to discover how to work with Mr. Carter. After his initial encouraging remarks following his New Year’s Eve visit to Tehran, he has not communicated with me at all,” the Shah replied.

The Shah feared Mr. Carter favored his deposition. He felt the nation of Iran could be kept from extreme turmoil if he abdicated in favor of the Crown Prince and supported the establishment of a constitutional monarchy.

The talk really proved to be an expression of the Shah’s concern about Mr. Carter’s apparent ambivalence related to Iran and the continuation of the monarchy. The Shah explained he had attempted to communicate further with President Carter following the New Year’s Eve gathering in Tehran, but his efforts had been rebuffed. The usual channels of diplomacy, the Shah reasoned, might involve too much prejudice either for or against him, and so he had decided to make his proposal through a private emissary.

At the conclusion of the brief conversation, the Shah asked me if I would represent him and his interests to President Carter in Washington, D.C. He wanted to discover, if possible, what Mr. Carter had in mind for him and Iran. He offered on the spot to abdicate in favor of the Crown Prince and conduct an election for the purpose of establishing a constitutional monarchy under the direct leadership of a prime minister.

I had been selected as the emissary since I served as the Managing Director of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in Tehran and had lived in Tehran for several years. I could hardly contain my excitement. I would be representing the reigning monarch of the ancient Kingdom of Iran, an honor I had never thought possible but had dreamed of for many years.

I readily agreed to make every effort to convey the Shah’s message to Mr. Carter. I explained that I was leaving for the United States within a few days to attend a U. S. Chamber of Commerce conference and would attempt to obtain an appointment at the White House through the U.S. Embassy prior to my departure.

I introduced the Shah’s request to the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and inquired as to whether an appointment could be arranged during my visit to Washington. After a couple of days, I was told that I should be in touch with the White House upon my arrival in Washington.

I flew to Washington and immediately telephoned the White House. Based on the response of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, I concluded I could at least make the Shah’s request known to Mr. Carter either directly or through the appropriate channel. My assumption seemed confirmed when I was told to be at the White House at a specific time on a particular day.

The morning I was to visit the White House, however, I received a telephone call to the effect that President Carter had been called away and the message I had would be best conveyed through the Iran Desk Officer in the U.S. Department of State.

I followed the White House instructions and met the same day with the Desk Officer. The meeting with the Desk Officer proved to be less than cordial. From the outset of the meeting, the officer displayed no interest in the message. In fact, he seemed very antagonistic toward the Shah and Iran, and I later learned he was not fond of either the country or its leader. I was finally allowed to give my message, but the officer immediately informed me that the U.S. Government had no interest in what the Shah was proposing or wanted to do. I was summarily dismissed from the Department of State. My attempt to serve as a private emissary of the Shah to the White House failed.

I sent a message to Tehran regarding my experience. There was nothing more I could do.

I returned to Tehran and to my duties at the Chamber of Commerce for some two weeks before Mahin, our daughters and I traveled to the South of France for a brief vacation. While in France, we heard about the burning of a movie theater In Southern Iran. The gossip was that the theatre had been set ablaze by the Iranian Secret Service in response to opposition to the Shah in the area. The precise motivation for the event and the people and/or organization may still be a mystery, but the event did cause a stir among Iranians vacationing in Europe.

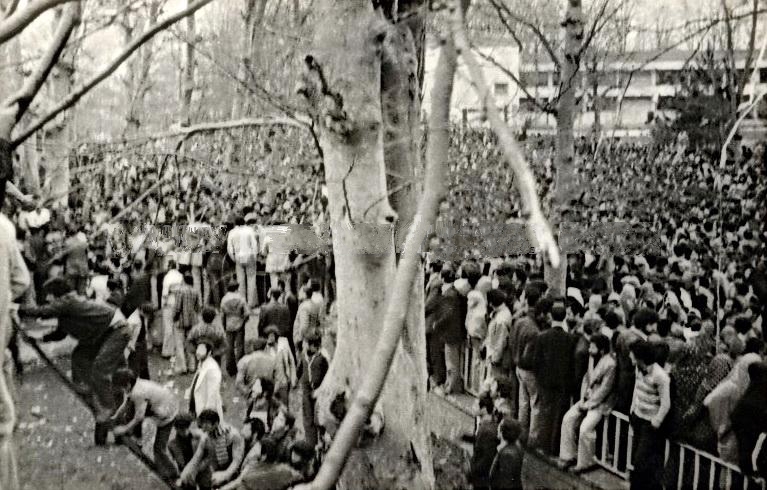

Upon our return to Iran, we discovered a substantial amount of unrest and anti-Shah activity in various parts of the country. Throughout the remainder of 1978, the level of unrest seemed to propel forward at an amazing speed.

Soon after the Revolution, the Iranian military and Ayatollah Kazem Shariatmadari sought the assistance of the U.S. Government in initiating a coup against Khomeini and the Islamic Republic. but was rebuffed. After the takeover of the embassy, the U.S. Government sent a member of the British Secret Service to my place of hiding and requested that I approach Ayatollah Shariatmadari to intervene on behalf of the hostages. The lack of trust with the US discouraged possible intervention.

About Franklin Burroughs: Franklin Burroughs, author and professor, lives in Concord. He lived in Iran for 15 years and served as the Executive Director of U.S.-Iran Chamber of Commerce. Mohammed Reza Shah Pavli attempted to inform President Carter of his willingness to establish a constitutional monarchy. Then after the Revolution, the Iranian military and Ayatollah Kazem Shariatmadari sought the assistance of the U.S. Government in initiating a coup against Khomeini and the Islamic Republic. In both instances, Burroughs served as an intermediary, before escaping and returning to the United States.

Burroughs is also one of eleven local authors participating in the just-released anthology of short stories, “Insight, Hindsight, and Flights of Fancy”.