by Nik Wojcik

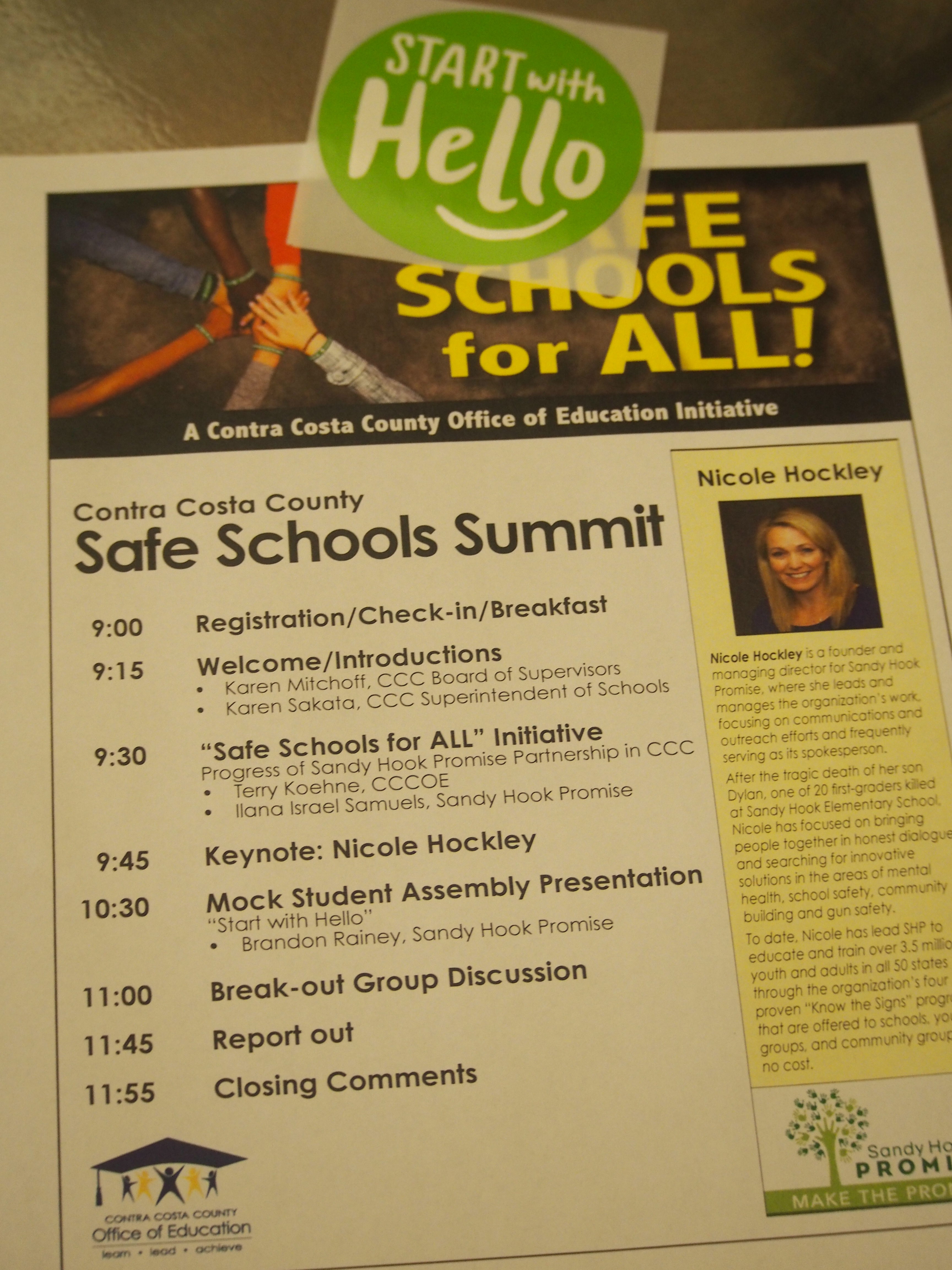

Over 160 people comprised of predominantly school administrators, and a handful of law enforcement and PTA representatives, gathered at Pleasant Hill Community Center on October 24 for the first annual School Safety Summit, a collaborative effort between Sandy Hook Promise (SHP) and Contra Costa Crisis Center (aka 211). It was a gathering of minds and a willingness to face the issue of gun violence in schools and learn about a program that seeks to prevent violence before it starts.

Nicole Hockley has experienced what no mother ever should. When her son Dylan died in the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in 2012, she was naive to the politics surrounding gun violence and to some degree, she continues to keep the divided political discourse at a distance. Her mission is not just about policy, instead, she’s doing everything in her power to save other students from the fate her son suffered.

Hockley represents one of three families that initially formed Sandy Hook Promise, an organization that put in the work to do what no other group seemed to be doing: to understand risk factors, what can be done to stop a threat before it becomes a tragic reality and to share that knowledge with schools.

After the events of Dec. 14, 2012, authorities swarmed Newtown and offered the community a crash course in the risk factors that lead up to school shootings. She became “furious” at the amount of information they had to offer, after the fact. She demanded to know why they weren’t out there teaching what they knew before tragedy strikes – she was told they just didn’t have the resources to reach every school, every parent, every student. So, she proclaimed, “If you can’t, we will,” and that is exactly what she and others incessantly travel from school-to-school attempting to do.

With each stop, she challenges schools to make and keep the same promise she has made: to not just fight gun violence in schools, but to save every student from harming themselves or others.

They devised a four-part program to offer schools nationwide. The information they present is heavily researched, and the programs they offer are measured for success. Resources to help implement and maintain the systems are given to schools free of charge. Sandy Hook Promise’s aim is simple: to ensure that every child put on a school bus comes back home alive. This summit was focused on giving Contra Costa County the tools to do just that.

Hockley told her own story and pitched her program that has already been implemented in 153 districts across the country. Her presentation included a video Titled “Evan,” that focuses on the life of a seemingly normal high school boy; but the crux of the story was the boy in the background, almost unnoticeable until he storms into the gym with a gun. It was a horrific and shocking visual – it was an effective dose of reality about the things we miss, the kids that go unseen.

Neither Hockley nor SHP’s next presenter, Brandon Rainey, demonize those students who may present a threat. They want people to understand that although mental health is an issue that needs to be addressed in this country, it is not necessarily a precursor to violence potential. “It’s an incredibly…small percentage of mentally ill people that go on to commit acts of violence,” Hockley said. “It’s much more likely they will become victims.”

The core belief at SHP is that every child can be at risk at some point or another and every child is worth saving. The method they have adopted is one of compassion and acknowledgment, which is at the heart of the first step in their program: Start with Hello. To explain further, Rainey led the room of adults on a journey back to their high school days, digging into the emotions of their younger selves. He asked people to raise their hands if they had “ever felt alone” and nearly every hand was raised.

Rainey explained that the kids most at risk feel alone, they feel invisible, and the best first step in preventing an at-risk youth from becoming violent is to just “Say Hello.” The focus at SHP is not on the guns, it’s on the people and they are encouraging school staffs, students and parents to refocus their energy on the individuals – the quiet kid who sits alone at lunch, who doesn’t seem to have any friends, who may be screaming out for help in the comfort of social media.

“Validating someone’s existence can have a massive impact,” Rainey explained. Admittedly, it may be awkward at first, but keep trying, because the most important part is showing somebody that you actually see them. The other three portions of the program involve recognizing the signs, safety assessment and an anonymous tip line they offer as part of their “Say Something” campaign.

Launched as an app in March, the Say Something project gives students a safe place to report concerns when they relate to potential suicide or violence. The Contra Costa Crisis Center will work in collaboration to address the anonymous tips and that information will be assessed on a case-by-case basis to determine what, if any, action is needed. The gist of the four-part program is simple: reach out, know the signs, say something and assess the threat.

Hockley and the great people of SHP came to Pleasant Hill to challenge our schools to make the promise, and according to an October 25 press statement, the Contra Costa County Office of Education has accepted that challenge stating that the SHP Know the Signs programs are “currently kicking off in middle schools and high schools throughout Contra Costa County.”

Hockley admitted that schools, in general, are safe from violence, but they’re not immune and Contra Costa County schools are thankful for the tools SHP is bringing to help keep our kids safe until “violence on school campuses becomes a thing of the past.”

After all, it starts with a simple first step: Say “hello.”

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERAOLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA